Lately, I’ve been seeing people on social media posting Topsters lists of their favourite video games, which...

lollipop chainsaw

Critical reviews are an endless source of discussion in popular culture. On the one hand, they offer...

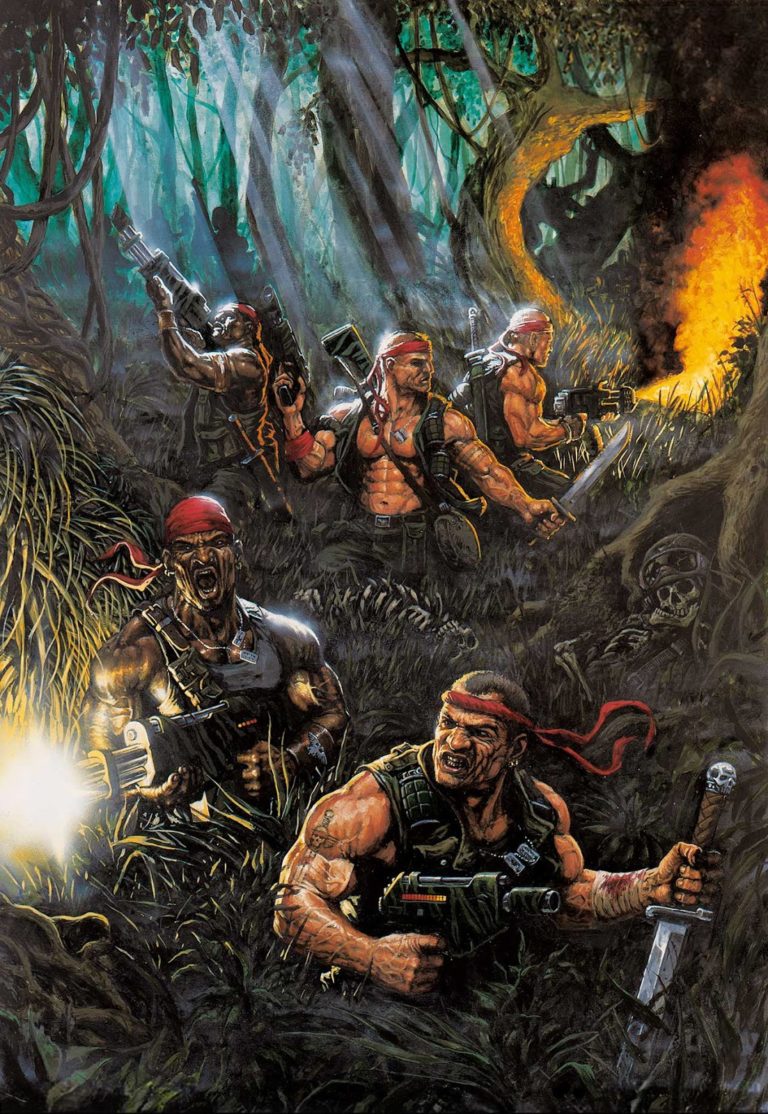

So I was recently reading this article on Polygon about unequal racial representations in gaming, and it...

In modern North American society, feminists have about as bad a rep as a man goosestepping down...