It’s been quite a while since my last retrospectives series (more than 3 years now), but that’s...

film

I may not be writing as much as I used to, but it’ll be a cold day...

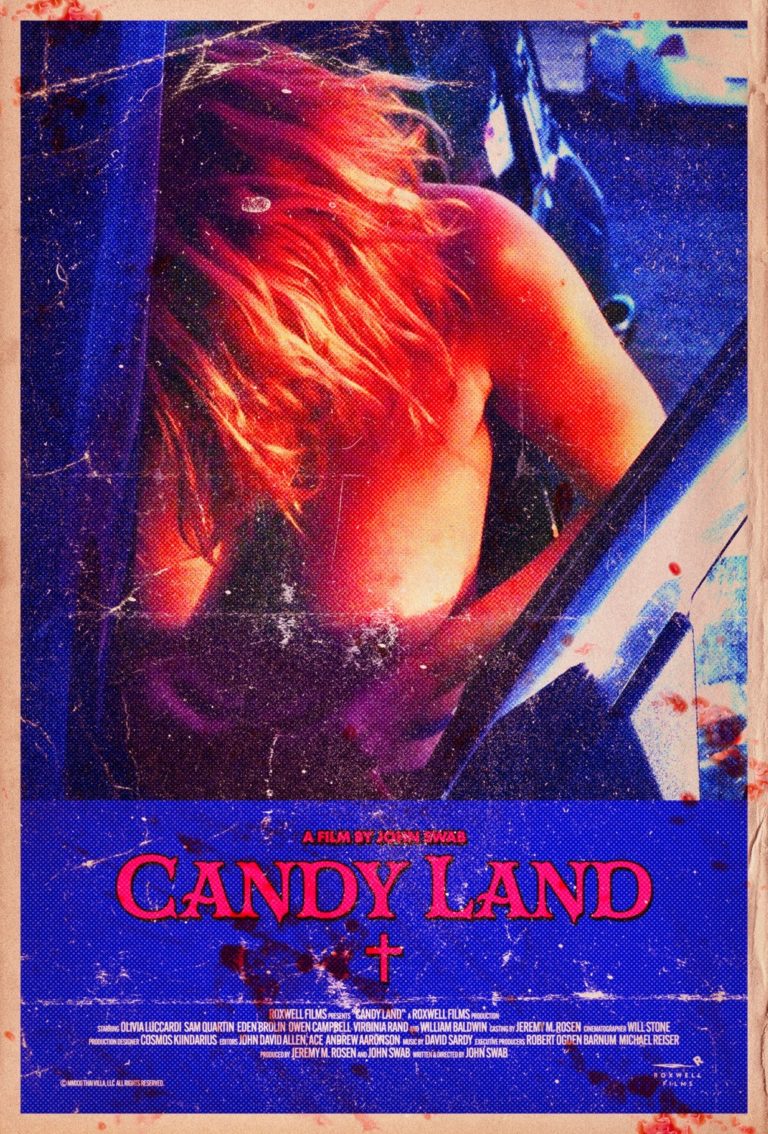

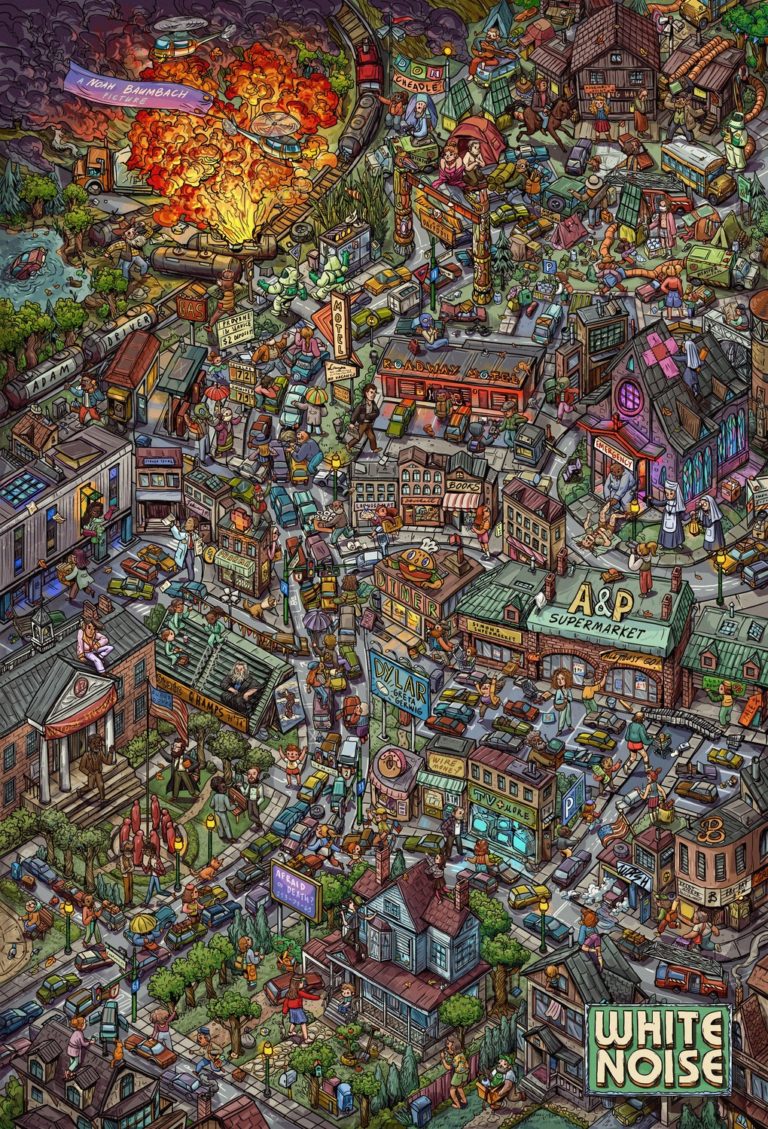

Welcome back to the mostly-annual year-end countdown of the best movie posters of the year! In case...

Welcome back to the mostly-annual year-end countdown of the best movie posters of the year! Obviously since...

Attack on Titan is one of those blockbuster series that you can expect even the most casual...

Godzilla vs. Kong was easily the most excited I have been for a movie since… well, since...

This review has been a long time coming. Like, to put it into perspective, I tend to start...

Welcome back to the Jurassic Park retrospective! In today’s post we’re going to talk about the most...

Welcome back to the Planet of the Apes retrospective! In today’s post we’re going to be looking...

Welcome back to the Planet of the Apes retrospective! In today’s post we’re going to be looking...

Welcome back to the Resident Evil retrospective! …yes, you read that correctly. It’s been more than seven...

Welcome back to a very special bonus entry in the Hannibal Lecter retrospective! In today’s post we’re...

Welcome back to the Hannibal Lecter retrospective! In today’s entry we’re going to be looking back at...

Welcome back to the Hannibal Lecter retrospective! In today’s post we’ll be looking at 2002’s prequel/remake/cash-in, Red...