And with that, we have completed another Love/Hate series here on IC2S! As soon as I finished...

objectivism

I recently replayed Bioshock and, having now familiarized myself with Ayn Rand and her ideology, it made...

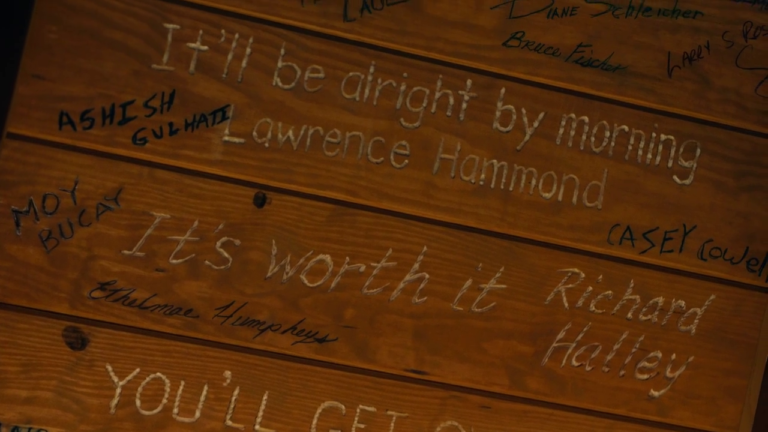

Welcome back to the Atlas Shrugged retrospective! Today we’ll be looking at the third and (mercifully) final...

Welcome back to part two of the Atlas Shrugged retrospective! In today’s post we’re going to be looking...

Hey it’s the 4th of July people, so what better way to celebrate than with a retrospectives...